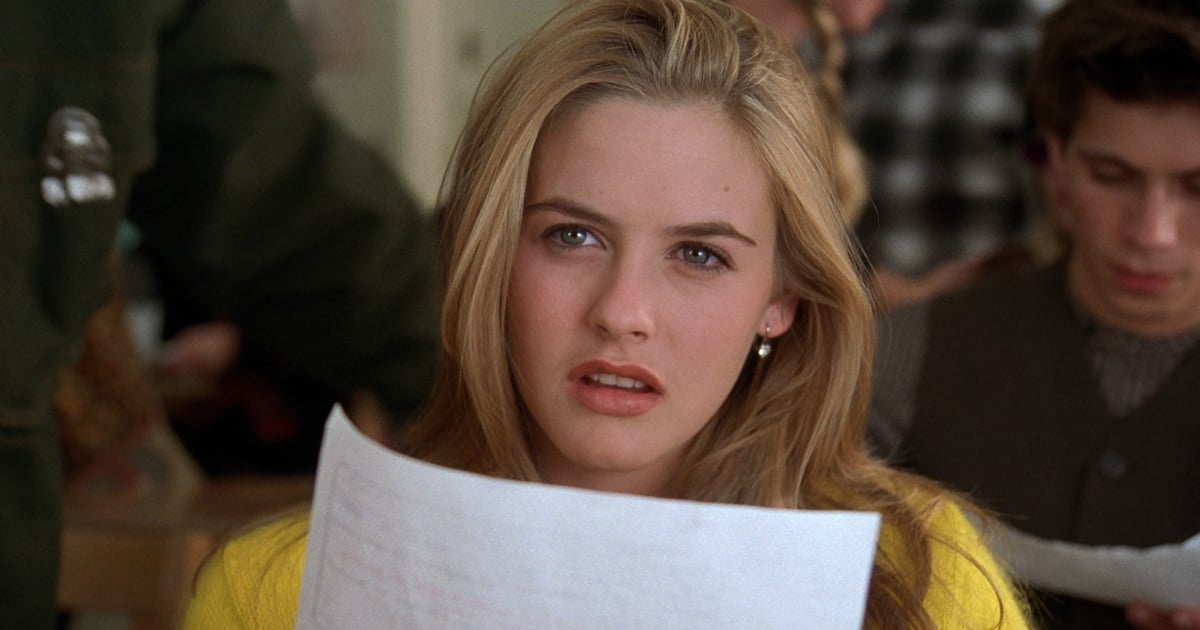

If you’ve seen the 1995 film Clueless, you’ll know it is many things: a teen comedy, a modern adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma, a gentle satire of Los Angeles ‘valley girl’ subculture that celebrates its heroine Cher Horowitz’s avoidance of responsibility.

It was also a forerunner of how we use the word ‘like’ today.

“Cher Horowitz in the film wasn’t a real character. She was an exaggeration of a lot of the features associated with young, female speech at the time,” says Dr Chloé Diskin, a sociolinguist at the University of Melbourne.

“But it obviously came from somewhere. Young women are nearly always the first people to do something new with language. You’ll find lots of popular articles online complaining about how young women never stop using ‘like’.

“We know through lots of different studies women were the first to use ‘like’. It started with young women; then it was taken up by young men, then by older women and then finally by older men.”

Dr Diskin says identity is integral to understanding how language changes over time but also adds that young people, particularly women, are crucial to understanding how that change occurs.

“I often compare linguistic innovations to fashion. Young women will be at the forefront of changes in fashion even if people have criticised them in the past.

“And I think it’s probably the same for this. Young people will always want to do things that are different to what their parents did.”