By the time my baby was three months old, I couldn't drive alone with her in the car for more than five minutes without pulling over to check she was still breathing.

I kept compulsive records of how much she drank, how long she slept and how many grams she put on each week.

I googled everything, obsessively.

I had a panic attack because I read that too many nights sleeping in a portacot can affect a baby's spine. I checked and double-checked the instructions on the baby carrier, terrified I was doing it wrong.

Watch: Dr Golly explaining how parenting changes the brain. Post continues below.

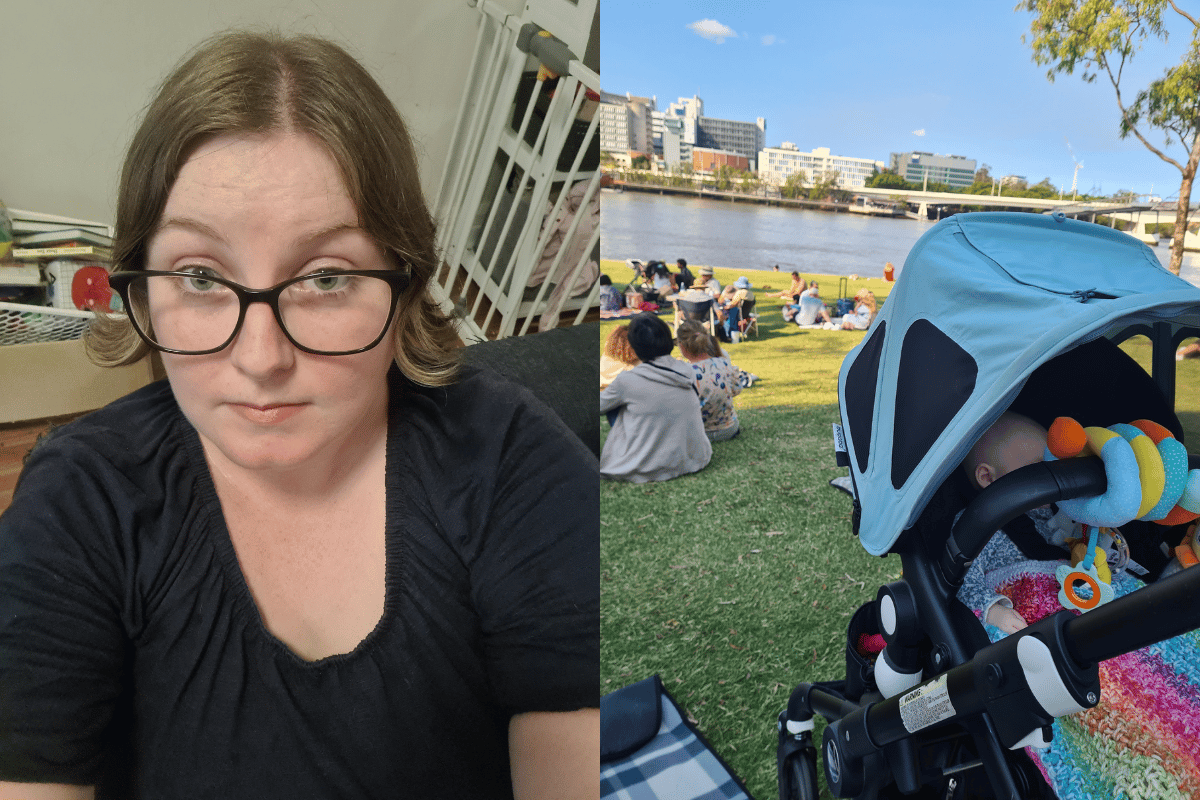

In short, I had an onset of postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder.

After a couple of rough years of infertility struggles, health complications, multiple miscarriages, a difficult pregnancy and less than ideal birth experience, I started my postpartum period already exhausted and already scared.

Everything felt like a danger to the fragile baby we brought home. I would hold her in my arms and cry, not wanting to put her to bed because I was so scared she would stop breathing in the night.

I thought this was just a normal reaction to finally having the precious thing I had wanted for so long. It made sense I was afraid to lose her. But these fears quickly took over my life and changed my behaviour.