On Australia Day 2024, Emily* settled in on her couch for the evening news. Her teenage son Scott* was away on what she thought was a boxing trip with friends. What she saw next would change her family forever.

There on her screen was a group of neo-Nazis holding a makeshift press conference, promoting white supremacy. Standing next to their leader, Thomas Sewell, was a boy in a black face mask and sunglasses. Despite the disguise, Emily knew immediately — it was Scott.

It was a devastating revelation for Emily, whose grandfather was a Dutch resistance fighter murdered by Nazis in a concentration camp.

"This is war," she told ABC's Four Corners. "You've literally started a war on my family."

Scott had been a typical teenager — passionate about music, books and sports. Quiet, intelligent, seemingly well-adjusted. But during the pandemic, Emily noticed subtle changes.

He began questioning the government's handling of COVID-19, developing increasingly right-wing political views.

"At first you think, 'Oh maybe he's got girl problems. Or is he getting bullied at school? Or is he struggling in class,'" Emily told ABC.

"I felt something was off and I couldn't pinpoint what. I did not think he'd be involved with a neo-Nazi organisation."

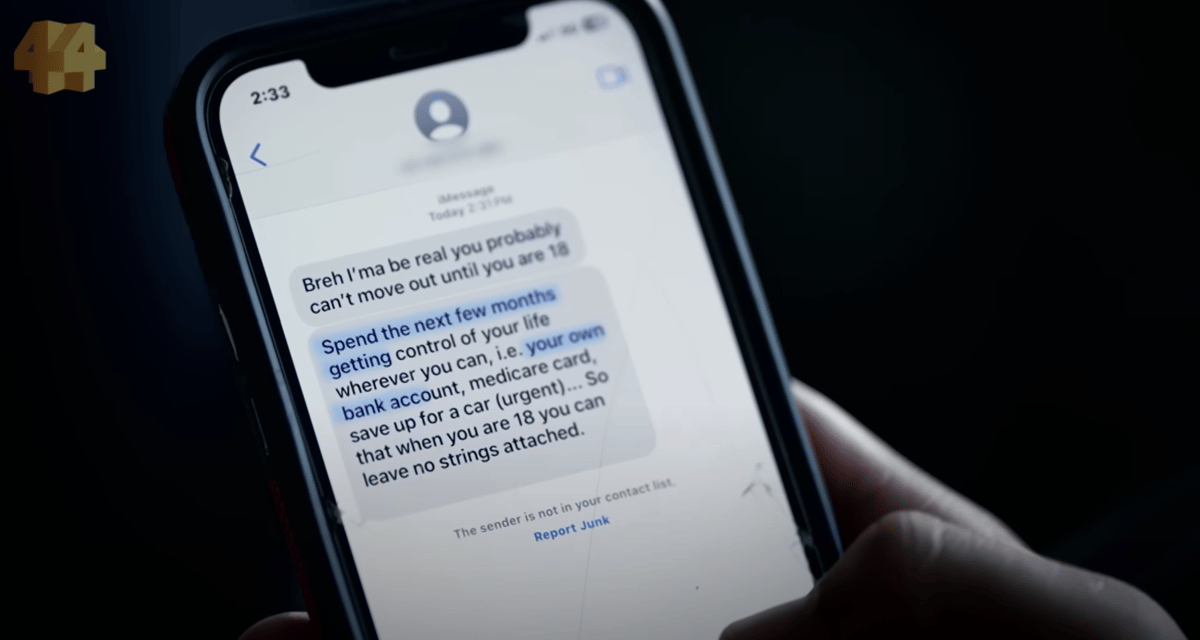

Unknown to Emily, Scott had encountered the National Socialist Network (NSN) — Australia's largest neo-Nazi group — at a rally against the Voice to Parliament. They drew him in with promises of boxing training and brotherhood during an isolating time.