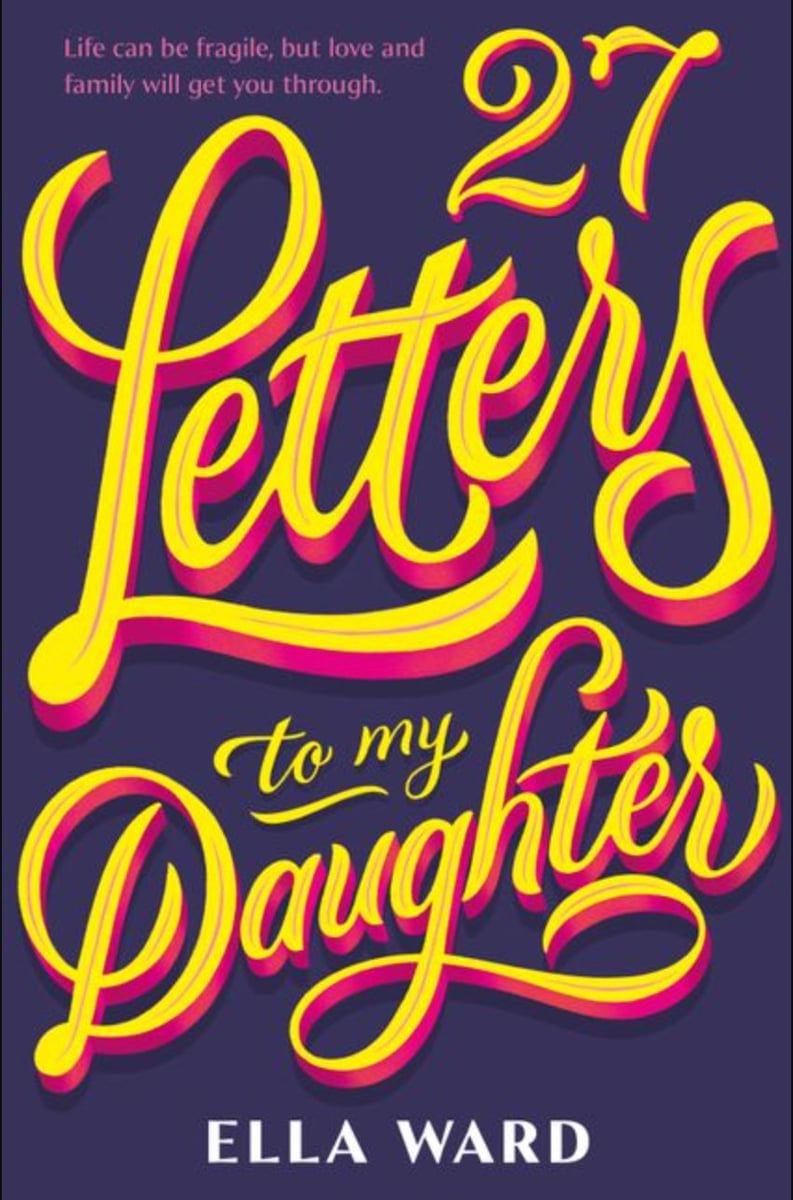

The following is an excerpt from 27 Letters to My Daughter by Ella Ward, a story of what we inherit, and how we become ourselves.

Life with a uterus is a life of bleeding. It is the uncertain beginning of bleeding; it is pretending we are not bleeding; it is the hushed cessation of bleeding. And it is the expectation that throughout we bleed, and smile. And smile, and bleed.

This is a letter about my bits, and the role my bits have played in my life. Which, I get isn’t what you may want from your mother, darling girl. Yet there will come a time when you are interested. When you do want to know. And that is what this letter is for.

When you’re being pursued by a pissed-off mountain lion, you don’t stop to worry about the blisters you might get running away. This is how it felt when I was told my cancer treatment would cause early menopause. I was sitting in my radiotherapist’s office having The Talk. The one in which they impress upon you how serious your cancer is, and how important your treatment is, and how there may be side-effects to that treatment.

We didn’t discuss the specifics in that appointment. Instead, we talked about the likelihood that I might die if I didn’t start treatment urgently. I was okay with this approach. I wasn’t thinking of the side-effects either. I was thinking of you, five years old, playground-bruised knees and a missing tooth, and how I would wrestle one hundred raging mountain lions if it meant I would be alive on the other side.

I was also pleased to be having this conversation with this particular specialist, because he had used the word 'vulva' and 'cervix' while maintaining eye contact. Which seems expected for a doctor, but, unfortunately, is not.