Lauren Gurrieri, RMIT University

Lingerie company Honey Birdette has been accused of “sexualising women” and its current storefront advertising campaign in suburban Australian shopping centres is described as depicting “soft porn”.

This latest scandal for the brand highlights the growing tension about the standards of sexual depiction considered acceptable in advertising.

Advertising in Australia is governed by a self-regulatory system in which a variety of codes are administered by the Advertising Standards Board. The board claims to represent community standards by appointing board members that represent a diverse cross-section of Australian society.

However, the system relies on consumers lodging complaints about advertisements to the Board which can only be made through the narrow guidelines provided. Yet even when consumers complain in droves about certain advertisements, such as the Ultra Tune advertisements that blatantly demean, sexualise and objectify women, complaints are often dismissed.

“Exploitative and degrading” depictions are not allowed under section 2.2 of the Australian Association of National Advertisers code of ethics, but questions remain about the adequacy of how these codes are interpreted and policed.

Exploiting loopholes and lag times

The lag time time between an advertisement being placed through media channels and the complaints process being followed means that the damage has already been done even if an advertisement is deemed to violate the code.

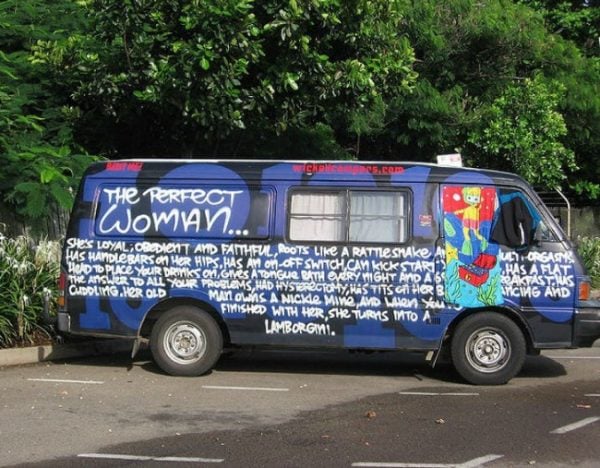

Companies are well aware of this, and often exploit this loophole as a way of generating further publicity for their brand. And as the case of Wicked Campers demonstrates, companies are not compelled to abide by the Advertising Standards Board’s decisions and can resume to business as usual, thereby calling into question the effectiveness of the process itself.