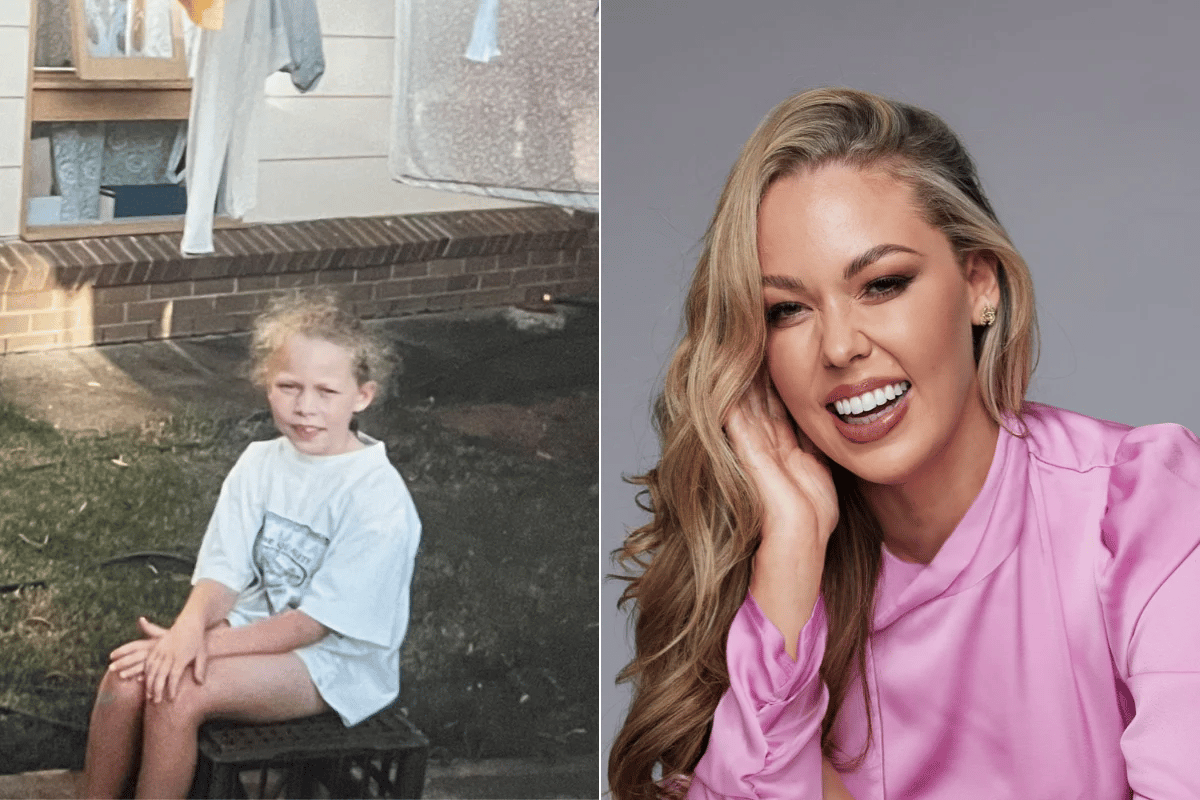

There's a narrative society loves to sell that people from "rough" postcodes are dangerous. We are damaged, somehow deficient, and destined to fail.

What "they" never tell you is the truth: behind the brick and cladding of housing commission homes are families full of grit, culture, loyalty — and to be frank — a bloody brilliance and resilience that is incomparable.

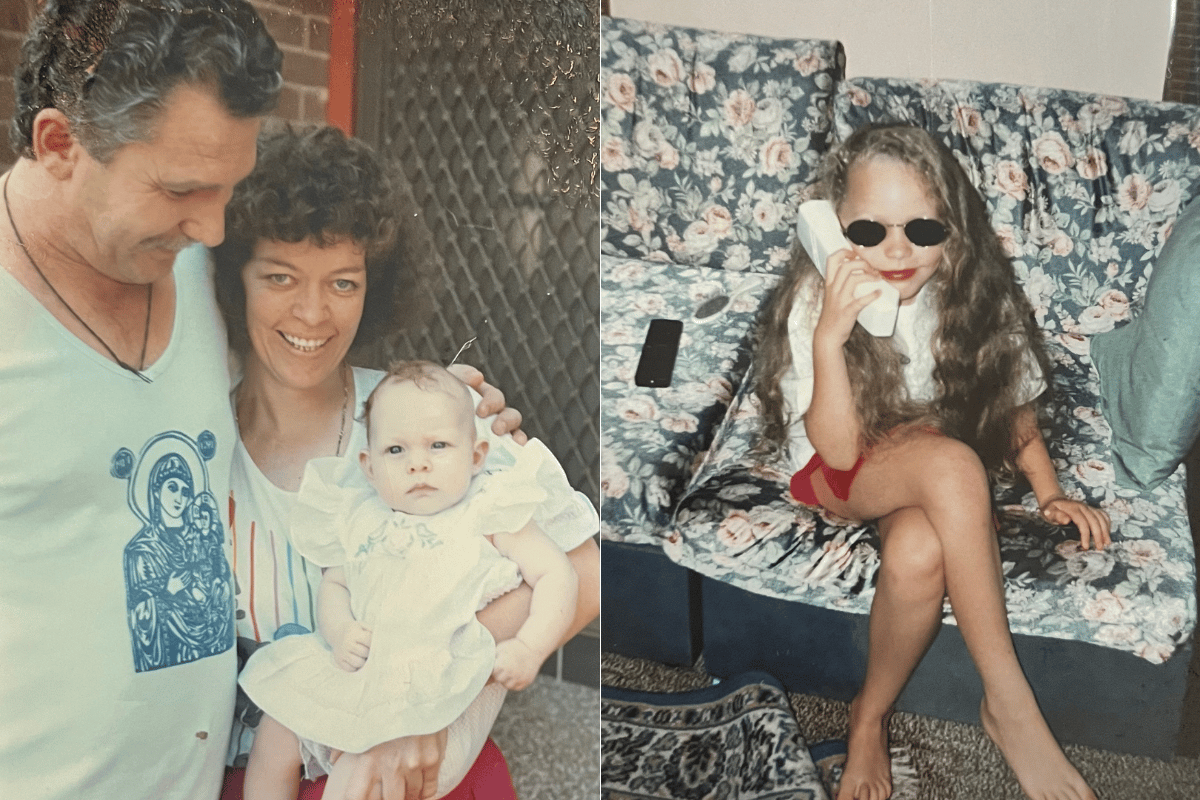

I was raised on Debby Way, a cul de sac in Toongabbie, a suburb of Blacktown in Sydney's Western Suburbs.

On Debby Way, the scent of burnt cheap sausages drifted through busted flyscreens. Kids rode rusted bikes with no brakes. Someone's cousin was always fixing a car that would never start.

But every backyard bonfire was hosted by real people, with a genuine desire to love and connect. They told solid yarns about where they'd come from and where they were going. They had big dreams that hadn't died yet.

Watch: We asked Aussies if anyone they know actually bought a house without help. Post continues below.

Blacktown was rough, no doubt about it. It carried the weight of colonisation, migration and neglect.