If you want to support independent women's media, become a Mamamia subscriber. Get an all-access pass to everything we make, including exclusive podcasts, articles, videos and our exercise app, MOVE.

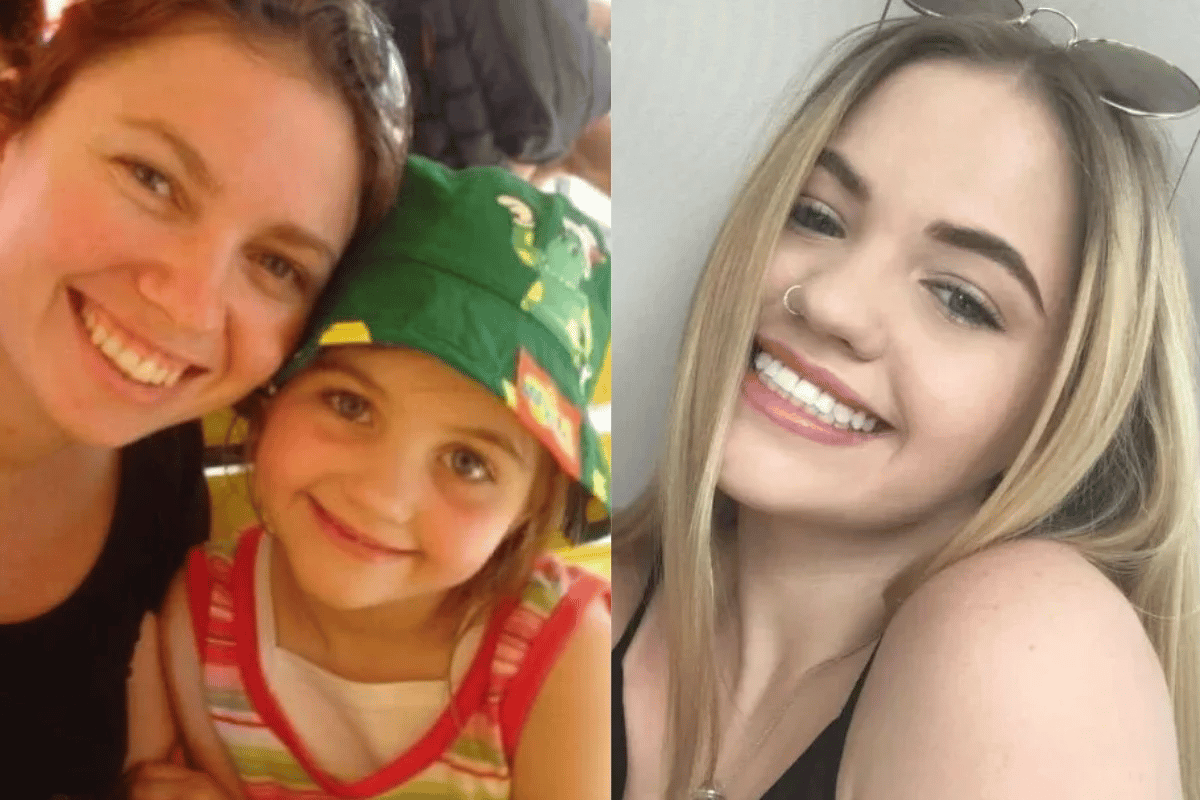

When my daughter was murdered by her ex-partner, our world spun violently. The grief, the disbelief, the hollow silence that followed — it was unlike anything I could've imagined. Her death is the worst thing that's ever happened to me. There is no comparing, no softening, no escaping that truth.

But in the months that followed, amidst the chaos of trauma and trying to piece my family back together, I discovered something deeply unsettling: that even in death, there is privilege. And I had it.

Watch: You Cant Ask That - Domestic And Family Violence Survivors Answer Why Didn't You Just Leave. Post continues below.

On the night my daughter was murdered, her son was delivered to us at 2am — in a singlet and a nappy. Nothing else. No clothes. No bag. No car seat. Just a traumatised child in the middle of the night, and a family now in shock trying to figure out what to do next. We live in a town where nothing is open at that hour.