This article originally appeared on Clare Stephens' Substack, NQR.

For the last year or so, I've intermittently received messages from people I know, or from people who know of me through my work.

The messages are usually along the lines of, "Um, is this you?" followed by a link to a video. Sometimes it's a version of the video from Facebook, sometimes from Instagram, sometimes from TikTok. But the gist is the same:

Watch Clare's thoughts on becoming a meme on Mamamia Out Loud. Post continues below.

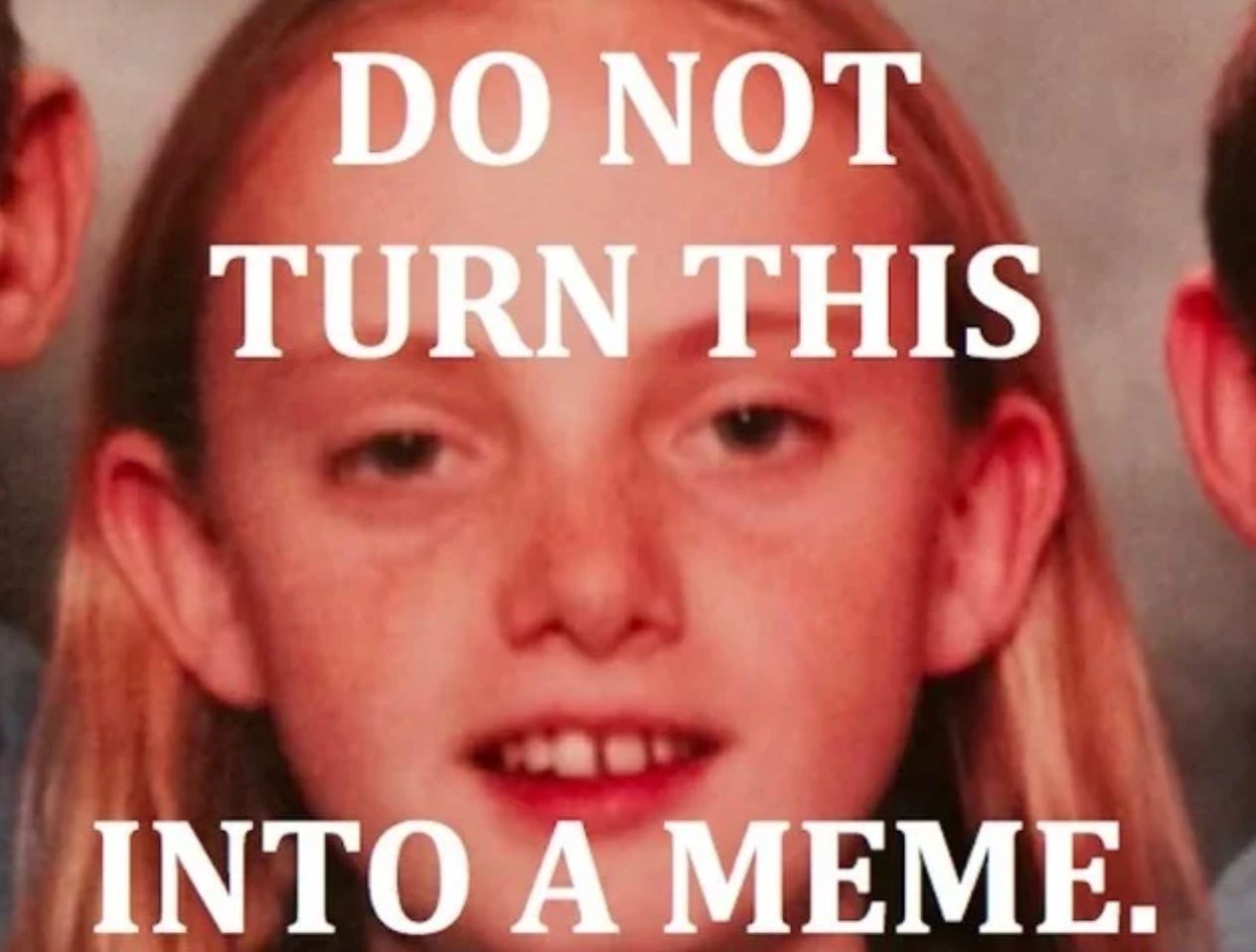

It starts with a photo of a rather unfortunate-looking child.

Glasses. Bad hair. Crooked teeth. The text below the photo reads: "to the guy who kept calling me four eyes in elementary."

Image: Supplied.

Image: Supplied.