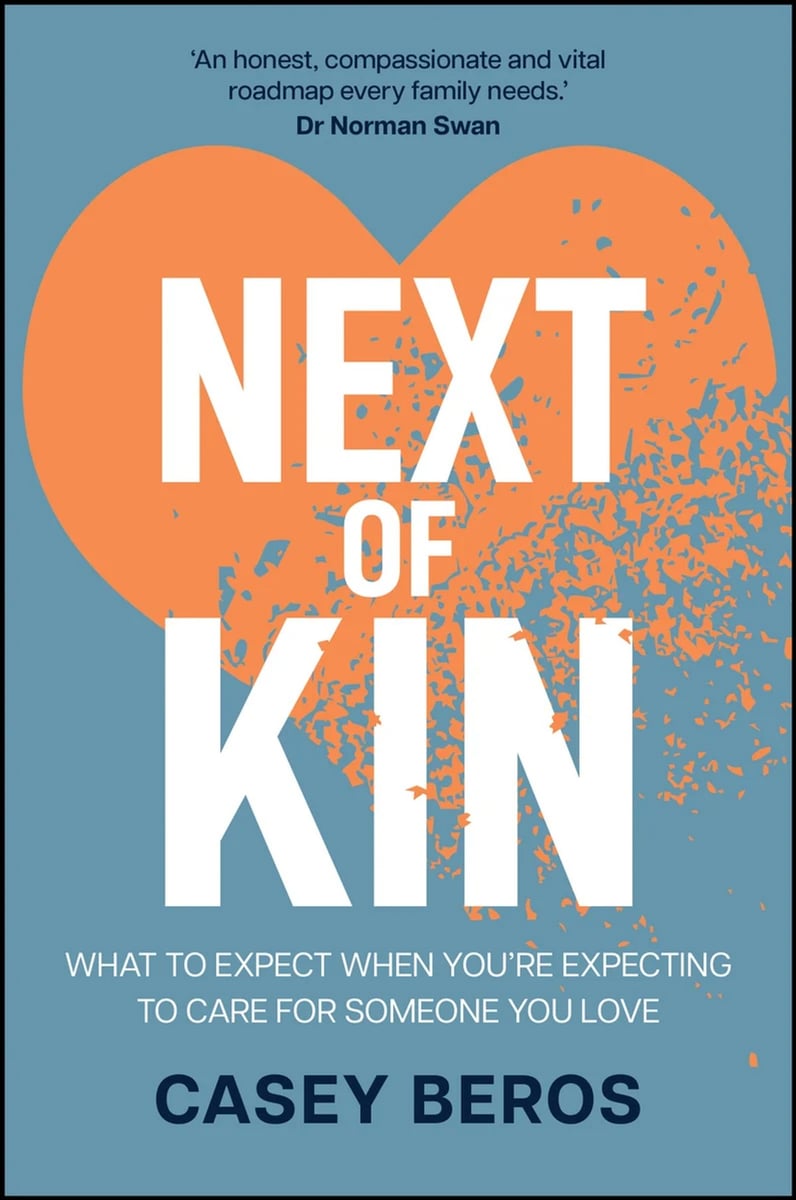

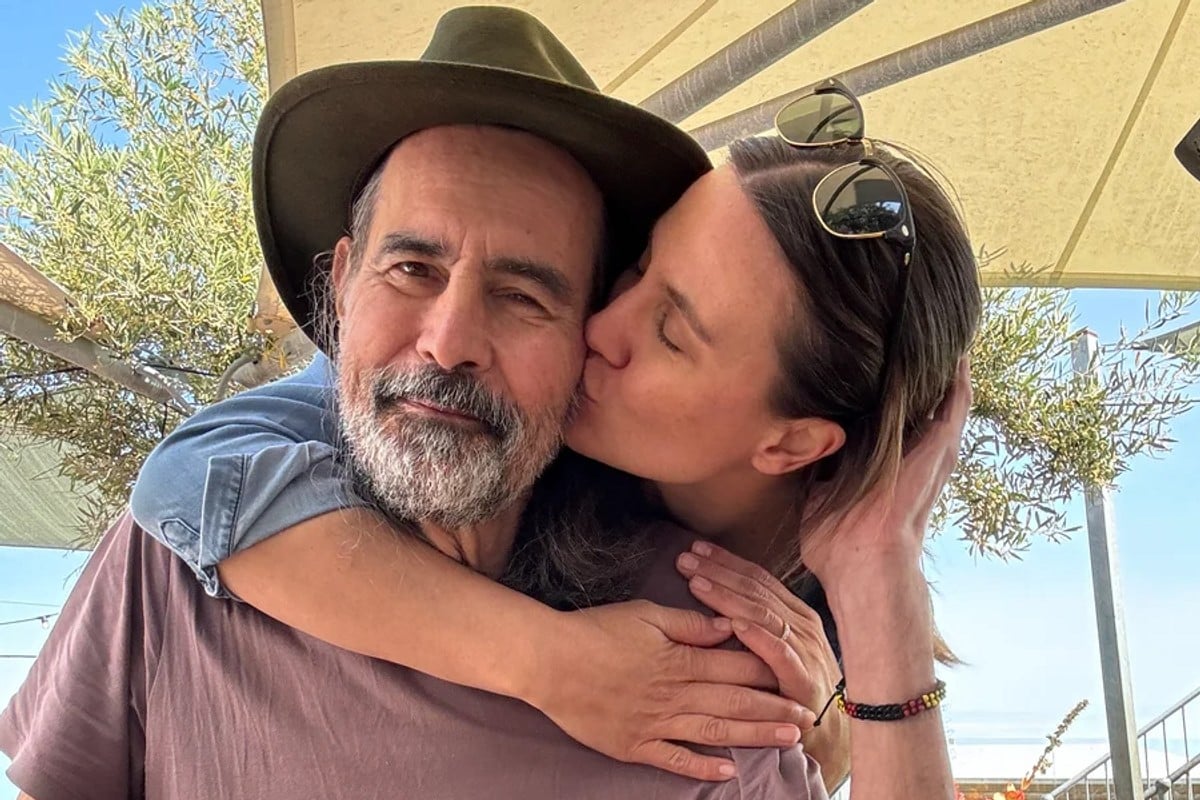

When Casey Beros learned her Dad was terminally ill, she moved her family across the country to become his carer. Casey's new book, Next of Kin: What to Expect When You're Expecting to Care for Someone You Love, shares her personal story and provides a heartfelt and practical guide to navigating the complicated world of care. In this edited extract, Casey talks about what it was like having a frank end-of-life conversation with her beloved Dad, Jack.

There is no word for the last month of Dad's life other than brutal.

In an extended state of what's known as terminal restlessness, Dad cannot be still. It's as though if he sits, sleeps or stops, death will catch him. So, we move. Day and night we walk anywhere and everywhere.

When Dad's feet are so swollen with fluid shoes no longer fit, we go barefoot. When the café gets too far, we push him in the wheelchair.

When getting out gets too much, we shuffle the hallway: up and back, up and back, up and back. To those watching, his body seems desperate to surrender to rest, but death is a fate his mind simply won't allow.

One night, after dark, we are on our third lap of the hospice grounds — Dad barefoot and arms interlinked with mine.

"Be honest with me. Do you really think I'm getting out of here?" he asks me tentatively.

I inhale into the space between his question and my response. I take a micro-second to consider my choices — be honest or tell a kind lie. Given we have spent a week in hospice and so far no one has said any of the 'D' words — death, dying, die, dead — I choose honesty.