New York’s Coney Island is world famous as a place of sideshows and carnival revelry, but this Brooklyn attraction also played a bizarre role in the birth of a now-vital piece of medical technology.

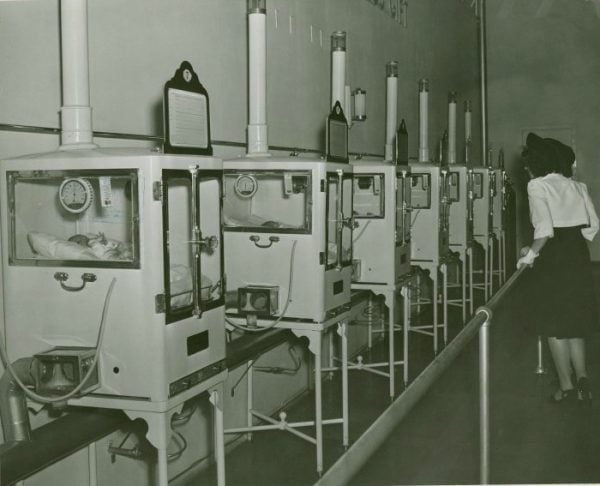

For among the sword swallowers and bearded ladies that lined the boardwalk in the early 1900s, lay a particularly unique exhibit: hundreds of premature babies encased in small glass cribs.

For a fee of 25c, punters could gawp at row upon row of these tiny, fragile infants, as they struggled through their first weeks of life. At the entrance, a sign read, “All the World Loves a Baby”.

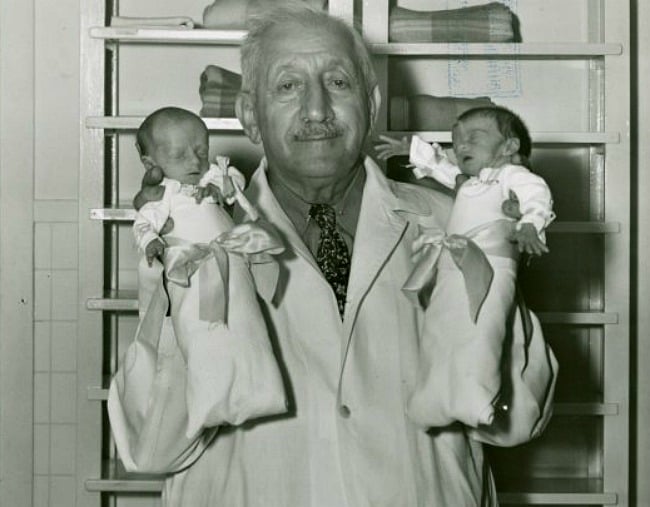

It was a freakshow attraction, yes. But this “child hatchery”, as its founder Dr Martin Couney called it, is believed to be responsible for saving the lives of as many as 7500 premature babies over its four-decade run and is credited as one of the first examples of a modern neonatal intensive care unit.

Martin Couney: showman or doctor?

Couney was – and remains – an enigmatic figure. Born in Prussia in 1869, he emigrated to the United States and opened the exhibit at Coney Island’s Luna Park in 1903 using incubators imported from France.

Couney purported to be protégé of Pierre-Constant Budin, the French doctor who pioneered the technology in the late 1800s, but according to The Smithsonian, no evidence has been found to support this, nor is there any record of Couney’s claimed medical credentials.

Yet for reasons unknown, this layman took it upon himself to show the invention to the world, to prove its life-saving potential to the then-reluctant medical establishment.