'Can I sue the 2000s for damages?'

That was my question after reading Lucinda 'Froomes' Price's book All I Ever Wanted Was To Be Hot, a forensic examination of self-image and western beauty standards set against an early 2000s backdrop. Smart, fierce and often very funny, the book explores the media-induced body dysmorphia that came to define the era, as well as Price's own eating disorders and relationship with cosmetic surgery. It left me breathless with rage.

To explain why, I have to use that all-too-ubiquitous pop psychology buzzword — 'triggered'. Price's book triggered me beyond belief, because like her, I also came of age in the 2000s (if by 'coming of age' you mean 'transitioning from 20 years old to 30', which I do). And I, too, was unhealthily obsessed with my appearance.

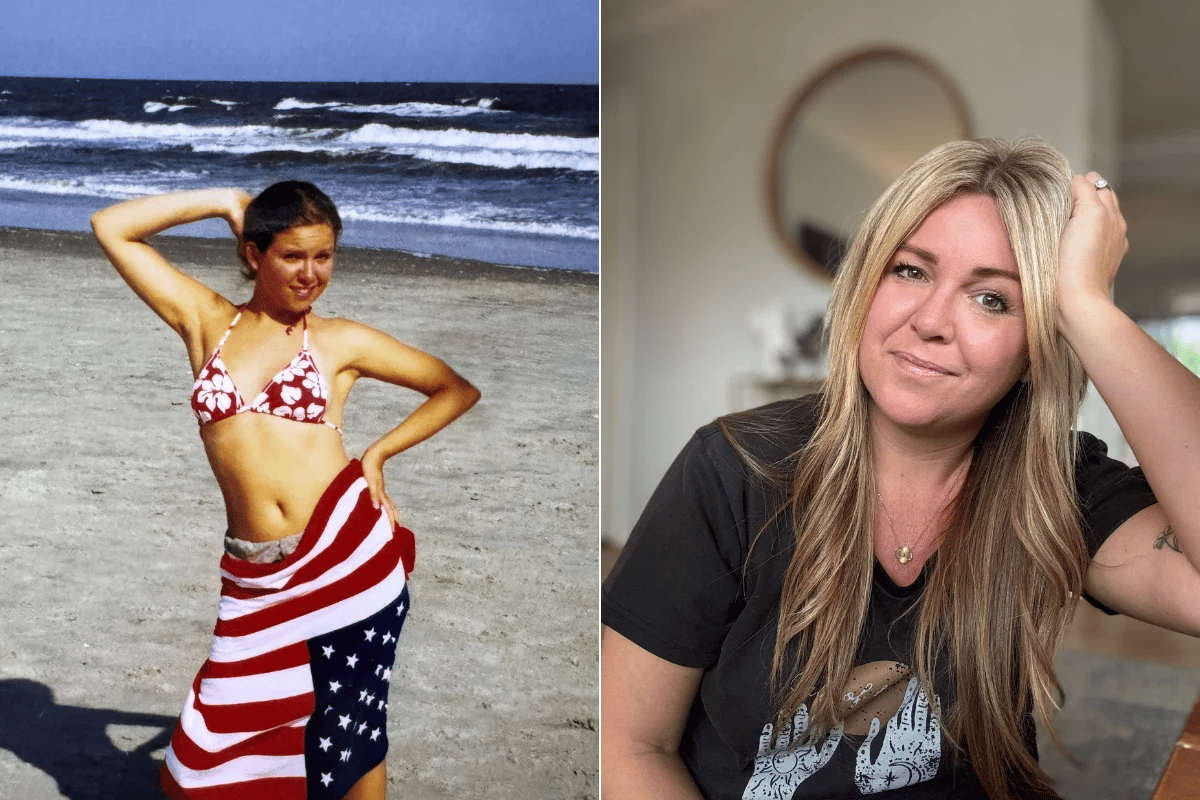

During the aughts, I felt overweight all the time, despite my size 10 figure. I constantly monitored my looks and appraised myself in every reflective surface — a habit I still can't break in my 40s. I caked my face in make-up and blasted my hair, first with scorching hot hairdryers and later, GHD straighteners. Lying in bed each night, I ran my hands over my belly, anxiously making sure I could still feel jutting hipbones at the bottom and ribs at the top. I purchased beauty products and magazines, hoping to buy my way out of ugliness.

During the aughts, I felt overweight all the time, despite my size 10 figure. Image: Supplied.

During the aughts, I felt overweight all the time, despite my size 10 figure. Image: Supplied.